What is a "Cost of Carbon" policy

The "Cost of Carbon" policy refers to a policy approach that assigns a monetary value to the negative externalities associated with the release of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere. This value, known as the "social cost of carbon" (SCC), represents the economic damage caused by emitting an additional ton of CO2 or its equivalent in other GHGs.

The aim of the cost of carbon policy is to internalize the environmental and social costs of carbon emissions, so that emitters bear the responsibility for the damages they cause. This creates an economic incentive to reduce emissions and transition towards cleaner energy sources.

There are several policy instruments that can be used to implement the cost of carbon, including:

- Carbon Tax: A direct tax on carbon emissions, often applied per ton of CO2 emitted. Companies and individuals pay the tax based on their emissions, creating an incentive to reduce them and invest in cleaner alternatives.

- Cap-and-Trade System: Also known as an Emissions Trading System (ETS), this method establishes a cap on total emissions allowed and distributes or auctions emissions allowances to companies. Companies can trade these allowances, providing an incentive to reduce emissions and sell excess allowances to others who are unable to meet the cap.

- Carbon Pricing: This involves setting a price on carbon emissions, which can be done through a carbon tax, cap-and-trade, or other mechanisms. The price signal encourages emitters to reduce their emissions and adopt cleaner technologies.

The choice of policy instrument and the level at which the cost of carbon is set depend on the specific goals and context of the implementing country or jurisdiction. The cost of carbon can be adjusted over time to reflect new information and changing circumstances, such as advancements in climate science or new economic analyses.

How are carbon emissions measured in order to be taxed

Measuring carbon emissions for taxation purposes typically involves a combination of direct measurement, estimation, and reporting. The process varies depending on the type of emitter (e.g., industry, power plants, transportation) and the specific regulatory requirements of the jurisdiction implementing the carbon tax. Here is a general outline of the process:

- Monitoring and Reporting Guidelines: Governments implementing carbon taxes establish monitoring and reporting guidelines for emitters. These guidelines set out the methods and requirements for measuring, estimating, and reporting emissions. Emitters must adhere to these guidelines to ensure consistency and accuracy in emissions data.

- Emissions Factors: Emissions factors are used to estimate the amount of greenhouse gas emissions produced by different activities and sources, such as fuel combustion, industrial processes, and waste management. These factors are based on the average emission rate of a given pollutant for a specific activity, and they are typically expressed in terms of mass of emissions per unit of activity (e.g., kilograms of CO2 emitted per kilogram of coal burned). Governments and international organizations, such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), provide emissions factors that can be used for this purpose.

- Data Collection and Measurement: Emitters are responsible for collecting data on their activities and emissions, which can include direct measurements (e.g., using emissions monitoring equipment) or estimates based on emissions factors and activity data (e.g., fuel consumption, production output). For example, a power plant might measure the amount of fuel it burns and use emissions factors to estimate the resulting CO2 emissions.

- Reporting and Verification: Emitters are required to report their emissions data to the appropriate regulatory body, following the established monitoring and reporting guidelines. This data is often subject to third-party verification to ensure accuracy and compliance with the guidelines.

- Tax Calculation and Payment: Based on the reported emissions data, the regulatory body calculates the amount of carbon tax owed by each emitter. The tax rate is typically set per tonne of CO2 equivalent emissions. Emitters are then required to pay the calculated tax amount, usually on a periodic basis (e.g., annually).

Who is responsible for carbon emissions measurements, the companies or the governments?

The responsibility for measuring carbon emissions primarily lies with the companies or emitters themselves. Governments establish guidelines and regulations for monitoring, reporting, and verifying greenhouse gas emissions, but companies are responsible for collecting the necessary data and accurately reporting their emissions according to these guidelines.

Here is a general outline of the responsibilities of companies and governments in measuring and reporting carbon emissions:

-

Companies' Responsibilities:

- Collect data on their activities and emissions, either through direct measurement (e.g., using emissions monitoring equipment) or estimation based on emissions factors and activity data (e.g., fuel consumption, production output).

- Implement internal processes and systems to ensure accurate and consistent measurement and reporting of emissions.

- Submit emissions reports to the appropriate regulatory body, adhering to the established monitoring and reporting guidelines.

-

Governments' Responsibilities:

- Develop and enforce regulations and guidelines for monitoring, reporting, and verifying greenhouse gas emissions.

- Provide emissions factors and guidance on estimation methods for different activities and sources of emissions.

- Review and verify submitted emissions reports to ensure accuracy and compliance with the guidelines.

- Take enforcement actions if companies do not comply with the regulations or fail to accurately report their emissions.

While companies are responsible for measuring and reporting their emissions, third-party verification is often required to ensure accuracy and compliance. Independent verifiers, typically accredited by the government or a designated regulatory body, assess the reported emissions data against the established guidelines and confirm its accuracy. This verification process adds a layer of accountability and helps maintain the integrity of the emissions measurement and reporting system.

What are Negative Externalities: The Hidden Costs of Economic Activities

Negative externalities are unintended and harmful consequences of economic activities that affect third parties not directly involved in the production or consumption of a good or service. These side effects result from market failures, where the costs of an activity are not fully borne by the parties directly involved, leading to an inefficient allocation of resources. This article delves into the concept of negative externalities, their causes, examples, and potential policy solutions for mitigating their impacts.

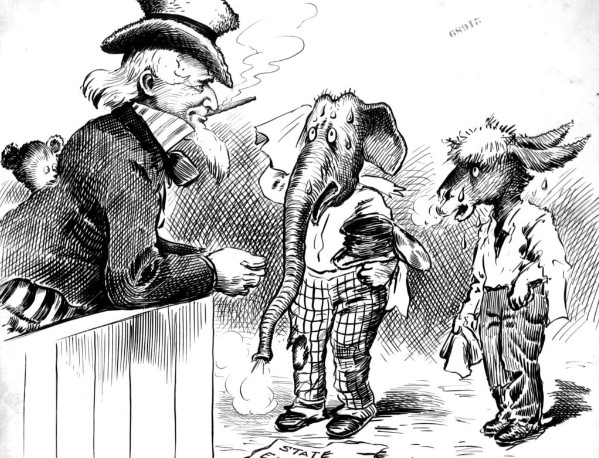

In a perfectly competitive market, the costs and benefits of economic activities are internalized by producers and consumers, leading to efficient market outcomes. However, when the actions of producers or consumers lead to costs that are not reflected in the market price, negative externalities occur. These costs are borne by third parties or society as a whole, creating a divergence between private costs (borne by the producer or consumer) and social costs (borne by society).

Negative externalities can arise in various forms, including environmental pollution, noise disturbance, traffic congestion, and public health issues. They result in overproduction and overconsumption of goods and services, as the market price does not account for the full social costs, leading to a deadweight loss and reduced overall welfare.

Negative externalities arise due to several reasons, including:

- Lack of property rights: When property rights are not clearly defined or enforced, parties may not be held accountable for the consequences of their actions, leading to negative externalities.

- Information asymmetry: Producers or consumers may not be fully aware of the consequences of their actions or the costs imposed on third parties, causing them to make decisions without considering the full social costs.

- Imperfect competition: In cases where market power is concentrated, producers may have the ability to pass on the costs of their actions to third parties without facing the full consequences, leading to negative externalities.

Examples of Negative Externalities

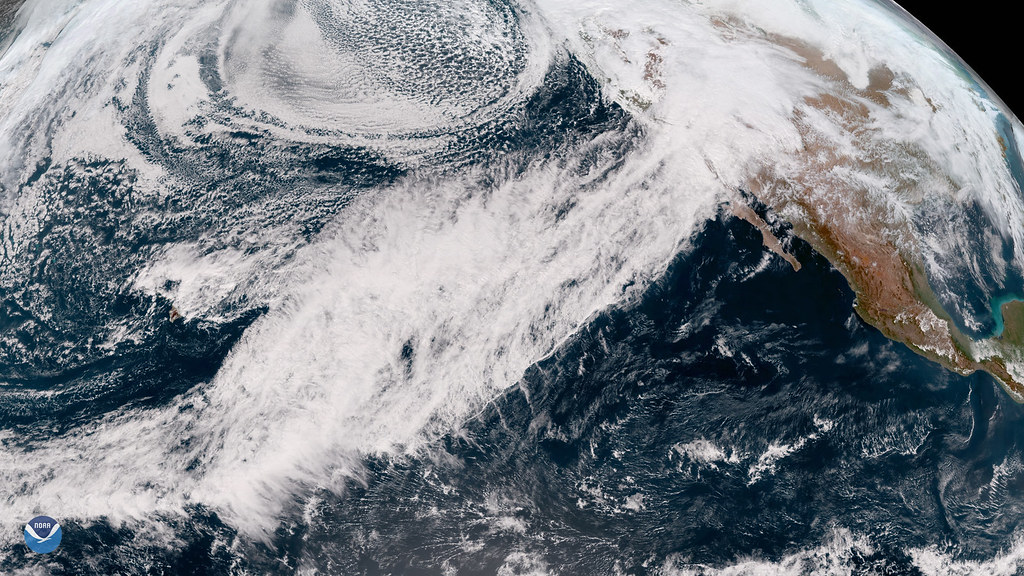

- Air pollution: Factories emitting pollutants into the air can cause respiratory problems and other health issues for nearby residents who do not benefit from the factory's production. This cost is not included in the price of the goods produced, leading to overproduction and overconsumption.

- Noise pollution: Loud music at a concert or construction noise in a residential area can disturb neighbors who are not directly involved in these activities. The cost of this disturbance is not borne by the concert organizers or construction companies, creating a negative externality.

- Traffic congestion: When a large number of vehicles use the same roads, travel times increase for all users, imposing additional costs in terms of time, fuel, and air pollution. These costs are not reflected in the price of owning or operating a vehicle, leading to overuse of road infrastructure.

What is Information Asymmetry: A General Explanation

Information asymmetry refers to a situation in which one party in a transaction or interaction possesses more or better information than the other party. This imbalance in information can lead to suboptimal decision-making, market inefficiencies, and a lack of transparency, potentially resulting in unfair advantages or exploitation.

In the context of negative externalities, information asymmetry can exacerbate the problem by making it difficult for parties to make informed decisions about the full costs and consequences of their actions. For example, consumers may not be aware of the environmental impact of a particular product, leading to overconsumption and resulting in negative externalities such as pollution or resource depletion. Producers may also lack information about the true costs of their production processes, causing them to impose unintended costs on third parties.

In business, information asymmetry can create situations where one party has an unfair advantage over another. For instance, a used car seller may have more information about the vehicle's history and condition than the buyer, leading to potential exploitation or the sale of a low-quality product at an inflated price. This phenomenon is known as the "lemons problem" in economics. Similarly, insider trading occurs when individuals with access to non-public information about a company's financial performance make trades based on that information, gaining an unfair advantage over other investors.

Government policies can be affected by information asymmetry when policymakers lack accurate or complete information about the issues they are addressing. This can lead to ineffective or poorly targeted policies, resulting in unintended consequences or a failure to achieve desired outcomes. For example, if a government lacks accurate data on the prevalence of drug abuse, it may implement a policy that fails to address the root causes of the problem or allocate resources inefficiently.

Regarding Environmental policy, the accurate assessment of environmental risks and impacts is crucial for effective environmental policy. However, information asymmetry can exist between polluters and regulators, with polluters potentially having more information about their emissions or the effectiveness of pollution control technologies. To address this issue, governments may implement policies requiring polluters to disclose information about their emissions, adopt specific pollution control technologies, or participate in emissions trading schemes that incentivize the reduction of pollution.